Every cruise stop on this trip involved interesting real life stories of kings and castles, art and religion, writers and warriors, triumph and tragedy. It is the the unfolding of the history of western civilization after the fall of Rome. But even though half of my genes came from the British isle, as an American all of the references are at least one stage removed from me. The kings are somebody else’s kings, the era was not my own, the soldiers came from some other place, and the battles were not my battles.

But once we reached Normandy, that all changed. Here MY country came to fight for the things we believe. Ellen’s uncle was in a plane shot down in the English channel during World War II. Another uncle of hers fought in the Battle of the Bulge. One of mine was a medic, serving in France. Yet another was on his way here when the war ended.

You may not know this, but the graveyard at Normandy is American soil, donated by the nation of France for us to honor our American dead, all of whom died in WWII in Europe save one. So it is that after the guide takes you to Omaha Beach, and you observe the large open area upon which all the German weapons are aimed; after you stare down the vertical cliffs which army rangers were forced to climb under fire; after you sit in a hardened concrete bunker and look around at the pockmarked landscape where we dropped bomb after bomb to try to clear the way; after you have marveled at the immensity of the task and the bravery that was required…

Only then, stepping on that American soil, does the the sight that opens before you have true impact. First, you see the giant Wall of the Missing, curving away from you on both sides. It contains the names and rank of over 1,500 soldiers whose remains were never identified. Some are buried here with markers that say “known only to God.” But this is just the preamble.

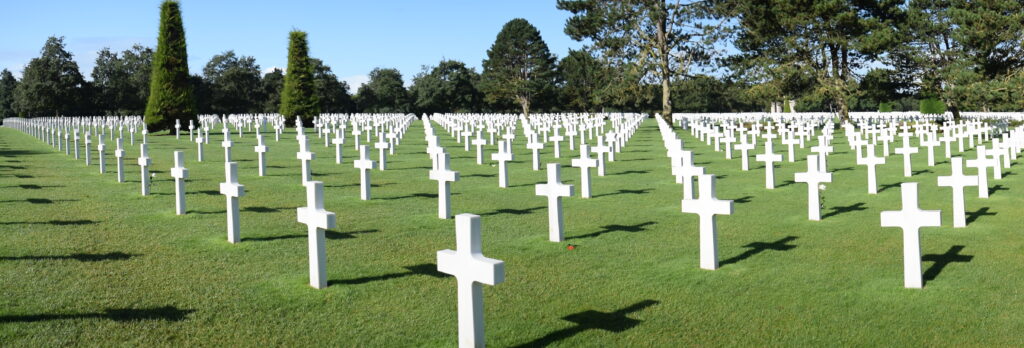

Beyond the statue representing the “Spirit of American Youth Rising from the Waves” is a raised concrete stage describing the battle and what followed. Beyond that stage is a reflecting pool, then a walkway that leads to a small circular chapel at the other end. On both sides of the walkway, extending in long, perfectly symmetrical order, are white crosses marking the graves of 9,388 soldiers and sailors. It is an immense cemetery and seeing it brings a reverent hush. We spent a long time walking on the grounds, taking in each detail: the stars of David for Jewish soldiers, the flags of the 6 nations involved, the inscriptions, the occasional Medal of Honor or other citation.

I choked up several times on this day: as I walked along looking at the names of the missing, again as I stood on the stage scanning the field, and yet again as I entered the small chapel at the end of the path. But the most emotional came at the end as we were leaving. We stood on the platform looking out over the peaceful sea of white crosses on a palate of green with the American flag flying gently in the breeze. Then they began playing some patriotic music. I don’t remember the song, but I remember the emotion. I struggled, but regained my composure. The song ended. Then…they played taps.

All I can say is, if you ever have the chance to go, you will not regret it.

By the way, the highest ranking person buried here is Teddy Roosevelt III, eldest son of President Theodore Roosevelt. Teddy and his younger brother Quentin served in World War I, and his brother was shot down and killed. Teddy, a general, was in poor health, but volunteered to lead a portion of the D-day invasion and was assigned leadership at Utah Beach. At 56, he was the oldest person to land on Normandy. His actions on that day led to a posthumous Medal of Honor honor.

A month after the landing, Teddy died of a heart attack. When it was decided he would be buried at Normandy, the Roosevelt family requested that the younger brother Quentin be moved to be next to him. That is why Quentin is the only non-WW II person to be buried here.

Peter, our French tour guide, was fantastic. A true student of history, he was an expert on every aspect of the tour,

From the broad expanse of Omaha Beach, where soldiers were surrounded on three sides.

To the steep cliffs of Point du Hoc, where Rangers climbed straight up, weathering fire from above,

To the heavily fortified German bunkers. All the ground indentations were from bombing raids from Allied troops. They had little impact on most of the bunkers.

To the church in the nearby town, where a paratrooper was caught on a spire. He survived.

But a replica dummy commemorates the event (although they moved it to the other side, because it is better for pictures.)

And the stained glass windows inside celebrate the “Avenging Angels” who saved their town.

The Wall of the Missing is sobering.

The reflecting pool and chapel.

A small portion of the cemetary.